Responding to Covid-19

Across the Faculty of Health and Medicine, staff and students have been engaged since the beginning with responding to the coronavirus pandemic. These are some of their stories.

The Faculty of Health and Medicine working in partnership with Lancaster Primary Care Network to deliver the Coronavirus Vaccine from the Health Innovation Campus.

Throughout one of the most difficult years imaginable, the Faculty of Health and Medicine has been on the frontline of the pandemic response. You can read about the work our students and staff have undertaken in the stories below. And as we close out 2020, we have again stepped up to contribute where we can to the fight against the coronavirus.

The Faculty is working in partnership with Lancaster Medical Practice (LMP) and Queen Square Medical Practice to deliver the coronavirus vaccine. Our Health Innovation Campus is the location for vaccinations for people living in and around Lancaster. This is made possible because of the strong relations we have with primary care providers across our local region. These partnerships can only strengthen over time.

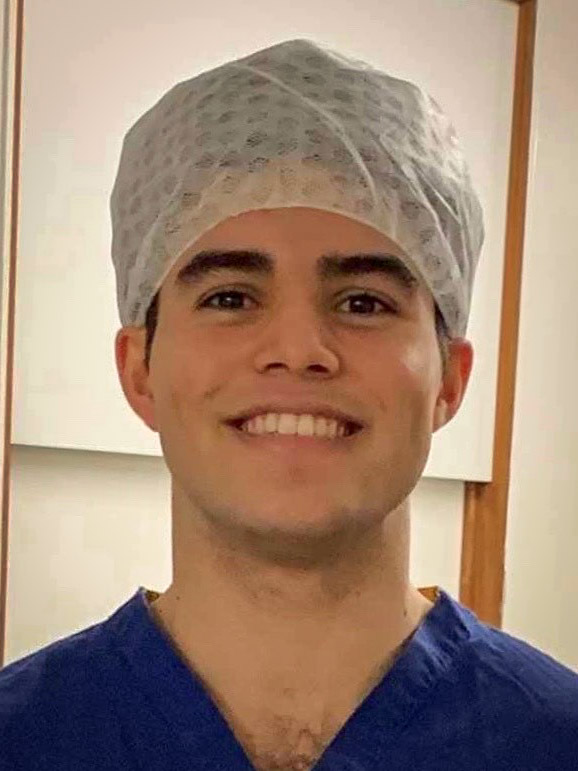

Professor Jo Rycroft-Malone

Vaccinations in the Health Innovation Campus

Listen to interviews with Professor Jo Rycroft-Malone, Dr Rahul Keith of Lancaster Medical Practice, and Eric Bevan, one of the first people to receive the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

-

Professor Jo Rycroft-Malone Interview

Listen to BBC Radio Lancashire's Tim Padfield interview Professor Jo Rycroft-Malone about the partnership that made possible the delivery of the coronavirus vaccine at the Health Innovation Campus.

-

Dr Rahul Keith Interview

BBC Radio Lancashire's Tim Padfield interviews Dr Rahul Keith from Lancaster Medical Practice about delivery of the coronavirus vaccine.

-

Eric Bevan Interview

Tim Padfield from BBC Radio Lancashire interviews Eric Bevan, 92, one of the first people to receive the new Pfizer/BioNTech coronavirus vaccine.

Lancaster Medical School

Lancaster Medical School's place is at the heart of the community, with strong ties to our local hospitals and NHS trusts. During the pandemic our staff and students have been working on the frontline of healthcare services, providing invaluable support in a time of crisis.

Learning leadership skills in a time of crisis

Lucy comes from Oxfordshire and has just completed the Foundation/Gateway Year for Medicine at Lancaster. She will be starting her first year of Medical Studies this September.

While always interested in the sciences and anatomy, her passion for Medicine really took hold during her Year 10 work experience at a care home. Interaction with the residents might have only been sitting down and talking to them for a while but even that can mean so much. She began to volunteer there, setting herself on the path that would lead her to studying Medicine at Lancaster.

She went home for Easter—like most of her peers, with just a couple of text books—assuming that term would be resuming as normal. But lectures were cancelled and so she again went to work at the care home, now as a medical student and able to contribute far more to the care side. She quickly found new confidence in working close to the residents, providing personal care for very vulnerable people.

It was the beginning of a very challenging time at the care home. Whereas before the lockdown, residents might look forward to seeing family for lunch, now they weren’t allowed any visitors, and for many it was very hard to grasp what was going on. Many ways of working changed over this period: From having to wear full PPE all the time, keeping physically distant from the residents, unable to stay and chat with them, to adopting a ‘barrier nursing’ operation where all doors were closed all the time. A very difficult and isolating time for the residents.

These were vulnerable people with underlying health conditions, so when positive cases of Covid began to show up amongst the care home population, it was really awful with many residents dying. And dying without family members surrounded by carers whose faces they couldn’t see.

Lucy has found though, that over this terrible time she has developed her communication skills, her abilities to empathise with people, and more than anything her leadership skills. Though only a very junior member of the care team she was frequently in charge of the ‘floor’, managing multi-disciplinary teams of both regular and agency staff. This, along with developing her manual handling skills, has prepared her more than she can imagine for beginning her first year of Medical Studies at Lancaster Medical School.

A problem solver with a passion for public health

Charlotte has been a Clinical Support Worker (CSW) at the Royal Lancaster Infirmary (RLI) since her first year. It’s the CSW’s responsibility to look after the personal care of patients: It’s both good experience and one of the few jobs flexible enough to fit around the demands of studying Medicine.

Things began to change very quickly for her in early March. Placements were suddenly cancelled, then exams followed suit; her housemates (being international students) took the decision to leave for their home countries as travel restrictions began to be applied around the world. Knowing that she wasn’t at risk of bringing Covid home to anyone, Charlotte decided to pick up more and more shifts in A&E and the Respiratory wards at the RLI.

As the pandemic built, the work became more and more stressful, with one shift in particular where she, one other CSW and two nurses, had to manage a ward of nearly thirty patients by themselves. Nevertheless, her colleagues working full-time in the NHS, were all looking out for one another even more than usual.

Charlotte’s ambition to study Medicine stems from a love of challenges, a love that is seeing her apply to join the Army Medical Services after she graduates.

She is a problem solver with a passion for public health and health education.

Charlotte will be going into her fourth year this autumn.

It's been a reminder of why we study Medicine

There were about four days remaining on her second term placement at the Royal Blackburn Hospital when the placement was pulled due to the pandemic.

Rather than return home to Reading, along with a fellow student from London, Rachel made the choice to stay in Lancaster and assist however she could at the Royal Lancaster Infirmary (RLI). She applied to be a Clinical Support Worker and as a current medical student her application was fast-tracked. Over the two months she’s been a CSW, Rachel has worked across the hospital, from A&E and the Acute Medical and Surgical Units, to the Respiratory wards. Here she saw first-hand how Covid attacks the respiratory system, causing blood oxygen saturation to crash to levels that you just don’t see in living people.

It could have been scary, but coming off the back of 20 weeks working in hospital, and working with brilliant NHS professionals, she felt well prepared.

Working as a CSW has been an opportunity to make her a better medical student and ultimately turn her into a better doctor. The role of the CSW is delivering personal care, and this manual handling and basic patient care isn’t taught to medical students. Additionally, as a CSW/medical student, the ward doctors take the time to demonstrate procedures in a way that they normally would not.

This has been a time to put some of her learning into practice, and to be reminded why she is studying Medicine.

Rachel has just finished her second year at Lancaster.

Community pharmacies have been overlooked in the crisis

Sally is from York. She’ll be going into her fourth year when university resumes this autumn.

At the beginning of the pandemic, it was hard to take it too seriously. Sally was on a GP placement, and along with all of her friends at Medical school, she just assumed that it was an early break for Easter and they’d be back together in three weeks. But they haven’t returned to the University since.

Since then, and alongside her studies, Sally has worked at a community pharmacy, an area of the Covid response that has been overlooked and ignored during the pandemic. At the beginning of the crisis, the workload of her pharmacy increased dramatically, and they were dispensing hundreds of prescriptions every day.

This surge in prescribing led to shortages of some drugs such as steroid inhalers, or certain anti-depression medications. The fact that pharmacists are patient-facing, means that when a patient cannot get their prescription, some of them can become aggressive.

As a result of the demand, some wholesalers have increased the price of certain medications and these costs, at least in the short term, have to be borne by the pharmacists.

In all, though it hasn’t received any media coverage, community pharmacists have been under a great deal of stress and pressure during the crisis.

Community is incredibly important to her and so Sally wants to specialise in General practice with a special interest in psychology.

This was just a tragic situation

Isaac is originally from Brazil but moved to the UK when he was two, and after a stint in Kent, now calls Rutland his home.

He’s about to go into his fourth year and at the moment thinks his specialism choices will lead to a career as an E.N.T. doctor.

Isaac started working as a Health Care Assistant (HCA) at a geriatric mental health care home in January of this year. He combined this with his studies by mostly working nights.

As his obstetrics/gynaecology placement ended in March, and the Labour wards at the Royal Lancaster Infirmary were converted to Covid wards, he had to make a decision: Go home or stay and help at the care home, who were already struggling for staff. He decided to stay.

It was the beginning of a traumatic period in the care home: As Covid positive patients were brought in from hospital, so they infected a very susceptible geriatric population. Over the two weeks of the virus’s peak, 17 of 35 residents contracted Covid and died. Allied to this, staff began to get ill and had to self-isolate meaning fewer staff to deal with ever more challenging conditions.

But, rather than just let it get him down, Isaac has viewed this as a learning opportunity, albeit a tragic one. Now, in late June, he has taken a break to self-isolate for two weeks before heading home to see if help is needed in his local area.

Privileged to be able to help

Greta is originally from Slovakia. She read Biomedical Sciences at Bath before beginning her studies in Medicine at Lancaster. She has just finished her first year.

In between Bath and Lancaster, Greta did a gap year working as a Health Care Assistant in London at Barts Health Trust, principally at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. When the pandemic began, she could see from the Bank that her old hospital was crying out for support workers and so knowing that she wasn’t high risk, she moved back to London to assist.

Wards she had previously worked on were transformed into Covid wards to cope with the volume of patients; clinicians and nurses who were used to treating chronic illness were now required to help acute and critically ill patients. Her role as a Health Care Assistant was to help in any way she could; from manual handling to personal care, but she found that a great deal of her time was spent comforting patients who were scared and disoriented.

Only a few days before, many of these acute patients would not have known where their local hospital was; now they were being intubated and no one they knew was allowed to come and visit them.

Greta says that she felt privileged to be in a position to help; to support other health care professionals and the public in a time of crisis.

A positive outcome during a difficult time

Eabha has just finished her first year of medical studies. She is from North Antrim in Northern Ireland, and as the news broke that borders were going to be closed, she decided to travel home from Lancaster.

The run up to the Easter break saw her finishing a module on child growth before returning to Northern Ireland for what she was sure would be a three-week break. As such, she packed a bare minimum of two text books for study before class resumed. It soon became clear, however, that class would not be restarting on campus.

A workforce appeal email from the Northern Irish Health Service prompted her to apply to work as a Health Care Assistant at a care home where she had previously volunteered. This allowed her to work locally to where she lives.

Her role has covered all aspects of providing personal care, but a good deal of it is simply being there for elderly people during a time when they aren’t allowed visitors. This, though, highlights one of the worst aspects of dealing with the pandemic: Wearing face-covering PPE makes interactions with residents very impersonal. She worries that this lack of personal connection could be very psychologically damaging for residents.

A big worry has been the possibility that she might bring Covid into the home. This is an ever-present anxiety, and means being extremely vigilant and observing rigorous hygiene.

There are some positives, however. Time in the care home has made her reframe her career path towards geriatric medicine; the rapport that she has now with the staff and residents of the care home is incredibly strong; she lost a GP placement to the pandemic, but this experience has more than made up for it; and she has experienced a side of medicine that would be missed through the degree programme.

And the refund of her rent enabled her to buy an iPad and so download the medical texts she had left in Lancaster.

Let them know that you are there for them

Lucy is about to go into the fifth year of her medical degree, though because of the pandemic, she still needs to take her fourth-year final exams.

In mid-March, she was coming to the end of her Paediatrics rotation in Furness General Hospital, and while news of the pandemic was everywhere, there was even then, a sense of denial that it was going to be a problem. She then moved onto her placement in Palliative Care in St John’s Hospice, but after only two days, the placement was pulled. She could see, as new patients were brought into the hospice requiring isolation rooms, that there was a building unease amongst the care workers, and that her being there was only causing them added stress. Placements were cancelled and all teaching moved online.

She decided to return home to Jersey and immediately volunteered at Jersey General Hospital, letting them know that she was a fourth-year medical student and detailing her skills. A couple of weeks later she was assigned to work Oncology outpatients. Patients coming in for chemotherapy or blood transfusions need screening for any symptoms of Covid.

Cancer patients are an extremely high-risk group and so bloodwork that before the outbreak was looked after by Phlebotomy, now took place in Oncology. Lucy was tasked with that, as well as assisting with bone marrow biopsies and PICC line insertions. From a skills perspective, it has definitely been a positive experience. She even had the opportunity to present on various Leukaemias to staff, mirroring the problem-based learning she would have been doing at Lancaster.

But there have been real challenges, too. Everyone needs to be screened before they can enter the ward. That means patients and their loved ones, even when they about to receive bad news regarding their prognosis. And delivering bad news while wearing a mask, when so much human empathy is conveyed by the face, or not being allowed to hold inconsolable patients, has been especially challenging. Lucy has found that her patient communication skills have improved: Simply by listening, giving patients space to talk or cry, and letting them know you are there for them, is sometimes all you can do. And that is often enough.

Prior to working in the Oncology department, she had not considered it as a specialism, but now she finds that the fast pace of change and continually improving patient outcomes is making her seriously consider pursuing it as a career path.

A real appreciation for the whole NHS

In common with most of her peers, Deborah describes herself as being between years. The events that usually mark the end of an academic year haven’t happened, so she is a third year going into her fourth year when university resumes in the autumn.

Her home is near Harrogate and it is to there that she returned when it became clear that the country was about to lockdown in mid-March. Up to that point, she had been about to complete her obstetrics and gynaecology placement at the Royal Blackburn Hospital, but the week before that was due to end, everything stopped.

Before lockdown, Deborah had just finished her application to become a CSW at the Royal Lancaster Infirmary, and heading back home decided to repeat that application to work at Harrogate District Hospital. By the end of April, she was working as part of the hospital relief staff, two – three days a week, while she continued her medical studies remotely.

For the first month or so, she was assigned to a Frailty ward nursing frail and elderly patients with complex medical and care needs. This ward was classified Covid-red, meaning that all patients had been diagnosed with Covid-19 and consequently all interactions with them had to be conducted under full PPE. In the heat of the ward, manual handling in full PPE was no fun. But what Deborah really noticed was the isolation of the patients with whom she had to interact. They weren’t allowed visitors and her wearing a face mask and visor meant that simple things like smiling to express warmth, empathy, or compassion was impossible. She learned to take it slowly around those patients who found full-PPE intimidating and says that amongst the positives to come out of her time working as a CSW, are better interpersonal and communication skills.

Counterintuitively, being on a Covid-red ward isn’t as intimidating as you might imagine: Because you are in full-PPE all the time, your chances of contracting Covid are actually less than on the Covid-yellow wards, where PPE is less strictly observed.

Her ambition remains to push her career in the direction of Emergency medicine, but the experience of working during the pandemic has given her an immense appreciation of the work that the whole of the NHS does, and it has been a privilege to be able to help.

Wherever they need an extra pair of hands

Victoria is from Prestwich in North Manchester and by her own admission is a bit of a homebody. She fell in love with Lancaster’s campus atmosphere during a summer school and once decided, nowhere else would do.

In March this year she was combining campus-based teaching with her surgical rotation placement at the Royal Blackburn Hospital, and thinking ahead to her OSCE’s in June. Her rotation in surgical urology involved clerking, taking histories and performing simple examinations.

While on placement, it was the Junior Clinical Fellows (JCF) who first alerted her to the seriousness of the impending pandemic, and when her tutor didn’t show up for her PBL class, she knew something was really wrong. After teaching moved online, Victoria moved back to her family home in Prestwich and started to look around for ways to get involved in the Covid pandemic response. She has now worked as a band 2/3 Phlebotomist/Health Care Assistant for the East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust, mostly in Blackburn and Burnley, since mid-April.

During the pandemic she has worked wherever she is needed, for example Covid, urology, and paediatric wards. She’s worked on green, yellow, and red wards, the latter two requiring full PPE.

Working under Covid conditions is not easy: Wearing full PPE while caring for children who have sometimes been separated from their family can be especially hard, or working on the stroke ward with patients who often need to see facial expressions to understand fully what is being said to them. Working mostly nights, she’s witnessed some truly heart-breaking things.

But from horrible circumstances, there are still some positives to be found. Being alongside the nurses, she’s seen what it’s like to be much closer to the patients, and she’s been a part of everyone pulling together. And then there’s the support of the public: Lunch parcels with handwritten thank you notes from children; crocheted facemask extenders sent in by little old ladies. The public support has sometimes been a little overwhelming.

Victoria will be going into her third year when University resumes in the autumn.

Early graduation - Everyone pulling together

You look forward to graduating for the whole time you are medical student. The degree can be so challenging that looking forward to graduation can really keep you going. Megan was on the organising committee for the Medics Grad Ball, deposit paid to the venue, and everything …

In early March, Megan was on her Emergency Medicine rotation at Royal Blackburn Hospital’s A&E department. Patients were already coming in with possible coronavirus diagnoses, with paramedics arriving in full hazmat suits. This was before the seriousness of the disease was fully appreciated, and organising the hospital to cope was just beginning. It was a crazy time.

There were rumours flying around that final year medical students were going to be graduated early and sent to help out on the frontline as interim-Foundation Doctors (FY1) but no one really believed it was going to happen. Then one evening driving back from Blackburn, she got the email: That was exactly what was going to happen.

It was a very confusing time as they didn’t know where they were going to go. They were offered a choice: To be placed where they would have been sent in August, or remain working across the four regional hospitals (the Royal Lancaster Infirmary, Furness General Hospital, Blackpool Victoria Hospital, or Royal Blackburn Hospital). Megan chose to be placed where she would have gone in a normal year but even then, the way that regions and jobs are allocated, meant that she wasn’t certain of going to her preferred West Yorkshire. Luckily, she did, and was placed at Airedale General Hospital, just north of Keighley.

The move to Airedale was made a little bit easier by her Lancaster landlord who told her that going to help out on the frontline response meant she didn’t need to pay the last term’s rent. That bit of a financial cushion was a massive deal in helping her get set up.

Starting as an interim-Foundation Doctor (a role that had not existed before), in a hospital where all the current FY1 doctors had been redeployed, and everything was different, should have been incredibly challenging. But there was such a sense of morale, of everyone pulling together. Her new job was surgery, and just because of the way rotations had worked out, she hadn’t done a lot of it. Now, due to the cancellation of all elective surgeries, all surgery was emergency. But again, because of redeployments, Core Trainee surgical doctors had been moved back onto the wards (technically a step down for them), and so she got to learn from more experienced surgeons than might otherwise have been the case.

Getting used to a new hospital and new ways of working (computer systems, where things were) was made easier by an Advanced Nurse Practitioner who had been at Airedale for 11 years. He took the new graduates under his wing and made the transition as easy as he could.

Amongst the many challenges of working during the pandemic, one surprising one was a consequence of always working wearing a facemask: Being new in the hospital, and meeting so many new people all wearing masks, she found that she could spend a shift working alongside them, and then not recognise them in the canteen. But it’s a small thing.

What she’s really found is that Lancaster Medical School has prepared her better than she could have ever thought. On one of her first days on the job, concerned that she might not be able to cope, someone took her to one side and told her not to worry because ‘Lancaster makes great doctors’. And so it has turned out: Lancaster has ingrained in her ways of working and knowledge that she relies on every day. And having so much ward time in fifth year means she knows how to write a discharge letter, or put in a cannula – things other recent graduates might not.

Now, three months after starting at Airedale, Megan is about to begin her first job as a full FY1 doctor on surgical night shifts.

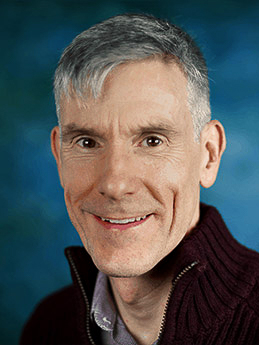

Dr Cliff Shelton - Training colleagues in the NHS

Cliff Shelton is a senior clinical lecturer in anaesthesia at Lancaster Medical School, and a consultant anaesthetist at Wythenshawe Hospital in South Manchester. When the COVID-19 pandemic was declared, the Medical School rapidly enabled Cliff to reduce his academic commitments in order to allow him to work full-time in his clinical role during the ‘surge’ of COVID-19 cases.

At Wythenshawe Hospital, Cliff used his experience of simulation-based education to help to train over 200 colleagues from the departments of anaesthesia, critical care and operating theatres in the safe use of personal protective equipment and COVID-19 specific procedures. He also participated in the process of rapidly developing and testing new organisational guidelines for the safe care of patients with COVID-19.

Subsequently, he was seconded to work on the acute intensive care unit as part of the team providing critical care to the sickest patients. As one of the busiest units in the North West of England, the Wythenshawe acute intensive care unit admitted over 70 critically ill patients with COVID-19, and achieved mortality outcomes much better than the national average.

As the first wave of the pandemic recedes, Cliff has returned to the Medical School to take on a new role as director of clinical skills and simulation. In this post, the experience he has gained in providing education to clinician colleagues during the pandemic will prove invaluable as medical education adapts to the ‘new normal’.

Though working full-time as a clinician during the peak of the pandemic, Cliff continued to make an active contribution to scholarship, particularly with regard to education, personal protective equipment, and novel clinical cases connected with the evolving pandemic. Cliff’s COVID-19 related publications include:

- Maintaining education and professional development for anaesthesia trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Self-isolating Virtual Education (SAVEd) project: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.046

- Computed tomography scanning in the prone position for a critically hypoxic patient with COVID‐19: https://doi.org/10.1002/anr3.12050

- Protecting staff and patients during airway management in the COVID-19 pandemic: are intubation boxes safe? https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.001

- Comment on the article by Dr T. Huda: Barrier Device Prototype for open tracheotomy during COVID-19 pandemic: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2020.06.004

- No doctor is an island: the ‘social distancing’ of guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic: https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11830

Collaboration on research and synthesis is one of the positives to come out of COVID-19

Dr Daniel Darbyshire is a Speciality Trainee in Emergency Medicine at Salford Royal Hospital and a NIHR Doctoral Fellow at Lancaster Medical School. His research centres around staff retention and sustainable careers within emergency medicine.

From looking at what was going on in the north of Italy over the early part of 2020, you could see that what was happing there was going to happen in the UK. While arranging his transition from mainly research back to clinical work Dr Darbyshire worked with the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, in his role as Emergency Medicine Trainees’ Association representative, on how medical trainees could best contribute and be supported through the pandemic. He also mentored junior doctors staying and rotating into the emergency department mid-pandemic.

Lancaster University and the NIHR were quick to approve his move from research for his PhD, to working full-time in the clinical setting; working nights and weekends, as required. With his PhD research paused, Dr Darbyshire found time to be able to contribute to a collaborative research synthesis effort. Working with mainly other emergency medicine trainees as part of the RCEM COVID-19 CPD team, he worked to search, sort and synthesise the increasing volume of research for the emergency physician on the front line. This collaborative approach to research and synthesis is one of the positives to come out of COVID-19– the challenge now will be to make it sustainable.

The Division of Biomedical and Life Sciences

Whether it has been research into a vaccine, the development of mobile testing, or working alongside the local NHS trust to deliver real-time diagnostics, the Division of Biomedical and Life Sciences has been at the forefront of the coronavirus response.

Dr Muhammad Munir is a member of Expert Panels at the World Health Organisation

Dr Munir is universally acknowledged to be one of the world's foremost authorities on viral zoonoses (diseases that can be transmitted to humans from animals). As an expert on viral transmission, virus pathobiology, viral antagonism of immune responses, and host factors that limit virus replication, Dr Munir has been an essential figure in helping to understand this coronavirus.

Consequently, since the start of the pandemic in mid-March, Dr Munir has rarely been out of the news. He has been interviewed well over 200 times by news channels across the globe for his valued expertise and insight into the virus. In addition to his considerable media work, Dr Munir is a member of Expert Panels at the World Health Organisation, developed a rapid diagnostic device (the commercialisation of which is detailed below) and has designed a viable vaccine strategy. If the University has one person that we might call the face of our Covid response, it is Dr Muhammad Munir.

Dr Muhammad Munir leads research into Covid detection

A new COVID19 test kit that can detect the presence of the virus in six different individuals simultaneously in under 30 minutes, is one step closer to coming to market following a partnership deal with leading electronic, robotics and software companies.

Brunel University London, together with Lancaster University and the University of Surrey have joined forces with GB Electronics (UK) Ltd, Inovo Robotics and Unique Secure to develop an inexpensive, rapid, diagnostic test kit that can inform people if they have COVID-19 in under 30 minutes and make it widely available.

The new partnership deal will bring together industry and academic experts in the fields of electronic and software engineering, diagnostics, virology, robotics and artificial intelligence to fast track the development of a new COVID-19 testing kit.

It is envisaged that the portable testing device, which can carry out six highly accurate tests every 30 minutes, can be used in areas with large concentrations of people, such as care homes, sizeable employers and airports, to quickly determine if an individual has the virus. The results from the current virus detection tests normally take several hours to process.

The inexpensive nature of the portable testing kit will make testing for COVID-19 more accessible in developing countries, in which remote communities may not have easy immediate access to high quality medical facilities.

Clinical tests in three NHS hospitals will begin shortly to validate the performance of the SARS-CoV-2 test kit.

Professor Wamadeva Balachandran from Brunel University London said: “There remains an urgent need to develop testing for COVID-19 which is quick and inexpensive. This will enable those who test positive to self-isolate as quickly as possible, helping to reduce the spread of the virus.

“I am delighted that GB Electronics, Inovo Robotics and Unique Secure have joined us on this exciting project, their expertise will help accelerate the development of this test on a mass scale to minimise loss of lives.”

Mark Bullen, Managing Director at GB Electronics, said: “GBE is very proud and excited to be part of this innovative collaborative team project to develop an essential point of care rapid testing device in the fight against COVID-19. The opportunity to utilise our electronic product design and manufacturing expertise was something my team jumped at; using our engineering skills to help make a vital contribution during the Coronavirus Pandemic by dramatically increasing the availability of rapid and safe testing.

“Leveraging our previous experience in healthcare, medical and IoT, coupled with working with such a strong collaborative team of Universities and Industrial Partners, will ensure the successful launch of this diagnostic testing product.”

David Rimer, CEO at Unique Secure, said: “We are extremely proud to have been chosen to collaborate on this critical project and be the company chosen to deliver the solution so pertinent for the new emerging world we all now live in. Unique Secure’s solid experience in delivering innovation through technology development will ensure that this rapid point-of care diagnostic kit is made available to those facilities that most need it.”

Henry Woods, co-founder of Inovo Robotics, said: “We are very pleased to be involved in this important work with the three Universities. Many vulnerable people around the world have had limited or no access to fast Covid-19 virus testing during the pandemic, we see the potential to make a real difference in limiting the spread of the virus through this technology.

“We will be using our commercial experience in electronics design and manufacturing to bring a robust and scalable product to market as quickly as possible. We also intend to lever our expertise in robotics and automation to further help with sample processing and handling in the future. This would increase throughput further while removing operators from the hazard of potential infection - a key technology adapting our ways of working to live with CV-19 in the long term.”

An authority on viruses and virus spread

Dr Derek Gatherer began his career as a lab biologist but an early move to Liverpool John Moores University pushed him in the direction of computational biology and bioinformatics. He worked for a time on the Human Genome Project before moving to Glasgow in 2003 where he worked for the Medical Research Council Virology Unit. In all, he has spent over 17 years working on viruses and is universally acknowledged as an authority on viruses and virus spread.

Over the course of the pandemic Dr Gatherer has regularly been a go-to source for media. He was interviewed over 50 times in the early weeks of the pandemic by both local and international news outlets.

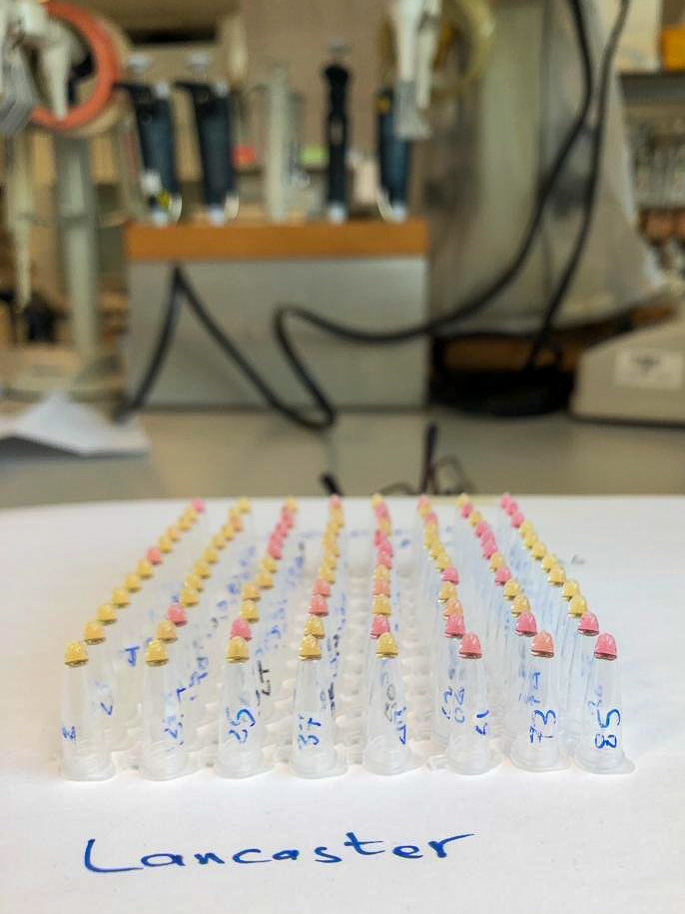

Biomedical and Life Sciences volunteers assist with rapid diagnostic tests

Lancaster University offered the use of its own labs in order to increase the number of tests for Covid-19 among NHS staff and patients following an approach from the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust (UHMBT).

University staff from Biomedical and Life Sciences (BLS) in the Faculty of Health and Medicine are now working with NHS staff from the diagnostic labs in UHMBT, using testing kits which are supplied by the NHS.

The diagnostic testing has been validated and the facility is now fully operational from 27th April.

Dr Shahedal Bari, Medical Director, University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust (UHMBT) said: "We were delighted that our partner and local university came forward to help us to carry out the tests. It is fantastic that the organisation with an outstanding track record of research and medical training, which trains many of our doctors of the future, has been able to help the population in this challenging time."

Professor Paul Bates, the Head of BLS, thanked everyone at Lancaster University who had volunteered to help the NHS.

“This is a really positive development that we can all be proud of, making a real contribution to fighting the Covid-19 pandemic.”

There is an urgent need to help both with rapid diagnosis of suspected Covid-19 cases presenting at hospitals as well as for NHS staff with possible infections. Being able to ramp up NHS testing may enable NHS staff to return to work sooner if the test is negative, while NHS patient samples will also be tested at the lab with a rapid turnaround.

Professor Bates said: “We are looking at running tests seven days a week, using equipment and facilities we have in the BLS labs, which will be a big help to our colleagues in the NHS. We have set up a main testing lab, with appropriate physical distancing measures, run by a team of BLS and NHS staff."

Professor Jo Rycroft Malone, Dean of the Faculty of Health and Medicine, said: "We have a strong track record of working closely with our regional partners. Collaborating with UHMBT to set up this testing lab at a time of national crisis shows the strength of our relationship, and how working closely together can really help our community."

Helping the NHS as a First Aider with the St John's Ambulance

Rhiannon Bates is helping the NHS during the Covid-19 crisis as a First Aider with the St John Ambulance unit in Lancaster.

Rhiannon, who is a Biomedical and Life Sciences student, joined the Lancaster University First Aid Society before volunteering with the charity where she qualified as a First Aider.

“Within a month, the COVID-19 pandemic broke out. In the following weeks, the UK entered lockdown – meaning that events such as festivals and football matches, where I would typically have helped St John Ambulance provide First Aid cover, were cancelled. As part of its plan to support the NHS in the fight against the virus, St John Ambulance provided volunteers with the unique chance of attending a COVID-19 specific training course, which I did.

“This allowed me to work alongside NHS staff and St John volunteers at Tameside Hospital in both the A&E department and some wards. The St John volunteers take the pressure off staff by doing patient observations, helping patients eat and drink and generally interacting with them when the nurses are too busy. Everything from working their bedside television to discussions about cats has happened during my time on the wards and getting to know patients like this is a privilege.”

Rhiannon began volunteering after both her final exams were cancelled and the NHS laboratory she worked with had a reduced workload.

“So far working with St John Ambulance is greatly rewarding. To be able to come home and know I have both learned something new and helped to make even a small difference in my local community is a great feeling. I am happy to put my time and effort into something so productive and rewarding and the public recognising the charity as a body there to help makes me proud to wear the uniform.”

Rhiannon plans to work for the NHS after graduation either in a clinical or laboratory role.

Division of Health Research

As we progress through the pandemic, it is becoming more and more apparent that the effects are more than just physical illness. The Division of Health Research is investigating how people's mental health has been affected by lockdown and isolation.

A time of momentous change in the NHS

Liz comes from Bournemouth but lives in Reading. She is a Consultant Nurse working with the hospital Palliative Care team at the Royal Berkshire Hospital. She has also just submitted her first year’s work for the PhD in Palliative Care in the Division of Health Research. Pursuing a PhD had always been something she’d wanted to do but it had seemed a slightly unobtainable goal, after completing her Master's in Advanced Practice, she applied to a job where having one was seen as desirable. The way it’s structured made Lancaster’s very accessible, so she took the plunge and enrolled 12 months ago, combining the blended learning PhD with full-time work as Head of the Hospital Palliative Care Team.

From the end of February onwards, things at the hospital began to change, repurposing the hospital for Covid over a very small number of days. Doing so much in so little time, managing change in a fast-moving environment, was very stressful but there was a kind of ‘wartime’ spirit that pulled everyone together.

It quickly became apparent that the though elderly patients were being admitted, they weren’t being referred to the Palliative Care team because they were getting too poorly, too quickly, so Liz found her role was more supporting redeployed nurses and being proactive about being visible on the wards so that she and her team could identify patients with palliative care needs.

National guidance on how to manage and treat Covid was changing very quickly, to the extent that a great deal of work was symptom management of patients who were too sick to be ventilated. Similarly, guidance on personal protective equipment in the first few days and weeks of the pandemic was changing: On non-Covid wards, there was no requirement to wear it, as asymptomatic transmission wasn’t clearly understood. A number of staff, including Liz herself, went on to contract Covid: A nurse and a doctor at the Royal Berkshire died as a result.

Nevertheless, the atmosphere in the hospital was at times akin to a war effort, with a sense that they were all part of something important; living through history. The hospital was incredibly supportive, focussed on wellbeing, and did a great job communicating through huge changes.

Her hope is that from the crisis the NHS will become more innovative, embracing different ways of working and technology. But she has a significant concern that people who should have come into hospital for other things (cancer, for example) didn’t as a consequence of the pandemic. As such, late diagnosis could become a very serious side-effect of lockdown. And for people who were in hospital and denied visitors, seeing only medical professionals in facemasks for months, there are likely to be serious psychological consequences.

And finally, working in the pandemic has caused her to reflect on her area of research, aligning it more with recent experiences.

Working in Palliative Care during the pandemic

For the past six years, Tania has been a Senior Lecturer in Palliative and End of Life Care at the University of Greenwich teaching nurses and paramedics. Prior to moving into academia, she was a Clinical Nurse Specialist and had just finished two years in the acute care sector. She is in her fourth year of study at Lancaster University, doing the PhD in Palliative Care.

As things began to get more serious through March and April, Tania was supporting her undergraduate students as they made the difficult decisions around working across the NHS frontline response. Doing so made her decide to return to work on the frontline herself: She intercalated her PhD for four months and went to work as a Clinical Nurse Specialist at the Heart of Kent Hospice.

Her work during the crisis has involved continued support of all her undergraduate students, whether they were working on the frontline of the pandemic response or not, alongside her work in the hospice. This volunteer role comprised managing the needs of 800 patients across the community, both in care homes and their own private homes; working on symptom control (pain, shortness of breath); liaising with GPs for prescriptions; liaising with paramedics on site to determine whether moving the patient from home was really in their best interests.

The pandemic changed the ways of working, with discussions of treatment escalation plans, and ceiling of care if the patient got Covid, all having to happen remotely. But, while these very difficult conversations had to happen over the phone, she was reassured by the fact that they were always putting the best interests of the patient first.

In February she published a textbook (Palliative and End of Life Care for Paramedics, Class Professional Publishing, Feb 2020), and over the pandemic has co-authored a handbook on the care of palliative patients in the community in the context of the pandemic. Due out later this year, all proceeds from the sale of this will be donated to the Hospice.

As the wave recedes, Tania has decided that she will continue to offer support at the hospice one day a week: Being involved in clinical work makes her a better lecturer, and the work has caused her to reconsider her PhD research question in the context of the pandemic.

Improving palliative care for people affected by the COVID-19 pandemic

The Division of Health Research, in collaboration with Kings College London, and York and Hull-York Medical School has launched a new project, CovPall.

CovPall is trying to understand more about how palliative care services and hospices are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, the problems that services and patients and families/those affected by COVID-19 are facing, and how to best respond.

Why does this research matter?

COVID-19 is a new disease (a lethal coronavirus) and has become a pandemic. Patient outcomes vary: Many people do recover after a mild form of the illness; some become seriously ill with very severe symptoms, and sadly some do die.

To support people in many settings, palliative care services and hospices have rapidly changed how they work, supporting existing patients who don’t have COVID-19, and also those with COVID-19 who have severe symptoms or are dying. In addition, the symptoms that people experience, and the best treatments for these symptoms, are not well understood.

Therefore, there is an urgent need to understand how palliative and end-of-life care services have responded to COVID-19. Learning from each other will speed up the responses and help future plans.

What do we want to find out?

We want to find out how palliative care and hospice services have changed and how their staff, volunteers and others have adapted their roles. We want to understand the challenges they face and the innovations and solutions they have implemented. We refer to this as Work Package 1 (WP1).

We also want to know what symptoms and problems patients have, how these symptoms change over time, what treatments/therapies are used and what seems to work best. We have referred to this as Work Package 2 (WP2).

Studying the impact of the pandemic on staff working in oncology departments

Dr Claire Hardy from the Centre for Organisational Health and Well-Being is the lead psychology researcher on the UK team looking at the impact of the covid-19 crisis on staff who work in oncology departments.

The team is led by The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in London and funded by The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity, with support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research.

Dr Hardy said: “It is a privilege to be working with the Royal Marsden on this important topic. The project will conduct essential research to help us better understand staff experiences of working in the NHS during COVID-19 and how we may be able to help them remain healthy and effective in their roles.”

The team hope the findings will help shape existing wellbeing initiatives and inform new supportive policies.

Those working in oncology face unique challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, which researchers fear could cause anxiety and stress amongst the workforce. Cancer patients are particularly vulnerable, with often complex treatment plans in place. Clinicians are making critical and difficult decisions daily, balancing the need to continue care, with the risks COVID-19 presents for cancer patients.

Chief Investigator, Dr Susana Banerjee, Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden and Reader in Women’s Cancers at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said: “Working in healthcare, our priority is the care and wellbeing of our patients. But when it comes to our own mental health, this is too often much lower down the list for us to address. We need to support all staff – not only those on the frontline – so that they remain well and committed to their work in the NHS to keep delivering world class care to our cancer patients. Wellbeing, resilience and reducing ‘burnout’ is fundamental to this.”

Call for palliative care to be adapted for severely ill Covid-19 patients

Emergency-style palliative care needs to be implemented to meet the needs of Covid-19 patients who wouldn’t benefit from a ventilator say researchers.

This is the first time that palliative care has been examined in light of the current global pandemic.

The researchers describe the challenges of providing palliative care where resources are stretched and demand is high, based on their experiences at a hospital in Switzerland close to the Italian border where there are high rates of the illness.

Professor Nancy Preston, Co-Director of Lancaster University’s International Observatory on End of Life Care said: “Many patients are too unwell to benefit from ventilation but still need their symptoms managing.”

In a paper published in The Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, the researchers explained how palliative care needs to adapt to an emergency style in order to help make the best decisions and support families.

Professor Preston said: “These people require a conservative approach to their treatment, one which provides maximum support for their physical, emotional and spiritual needs – this is where a recognition that palliative care is required is crucial”.

The team based their recommendation on caring for severely ill patients with Covid-19 in the Swiss hospital where treatment plans have changed dramatically.

This is due to a range of factors including competition for palliative care drugs, which are also used in ICU, as well as healthcare workers untrained in palliative care being re-allocated from their own specialities to care for patients with Covid-19.

“It is emergency style palliative care because patients can deteriorate quickly and need a rapid response from their health care team. It is crucial that patients with a high symptom burden are assessed and treated quickly – the recommendations in this paper based on front-line experience can make a difference. This approach is therefore being used across the hospital, and in emergency departments too.”

“Palliative care teams, intensivists and internal medicine specialists all work side by side as palliative care is recognised to be at the forefront of this crisis, as it can offer symptom management, support to families and spiritual care in a timely manner.”

The paper: “Conservative management of Covid-19 patients – emergency palliative care in action” is by Nancy Preston from the International Observatory on End of Life Care at Lancaster University and Lancaster PhD students Tanja Fusi-Schmidhauser and Claudia Gamondi with Nikola Keller from the Palliative and Supportive Care Clinic, Institute of Oncology of Southern Switzerland and Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale, Switzerland.

Using online diaries to capture public experiences of COVID-19

Lancaster University researchers from the Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast (ARC NWC) have recently completed a research study using online diaries to collect public insights of how the coronavirus affected daily life across the North West coast of England.

The research took place over 8 weeks (Apr-Jun 2020) and used diaries and weekly phone calls conducted by researchers, to capture public experiences during lockdown and the effects on health and wellbeing.

It was funded by the National Institute for Health Research, the nation's largest funder of health and care research, through its regional ARC NWC collaboration. The ARC NWC brings together the public, universities, NHS service providers and local authorities to improve the reach, quality and impact of research.

Fifteen public advisors were recruited to complete diaries from across the ARC NWC – advisors are members of the public who provide support to ARC NWC research, and live across the region.

A total of 115 diaries were completed and 114 weekly telephone contacts were made over the 8 weeks. A focus group was also conducted with participants exploring their experience of using diary methods.

The findings are now being written upon the following topics

- Effects on mental wellbeing such as the distress and anxiety caused by social separation. The positive ways that people have coped with the challenges of lockdown are also captured in the diaries.

- Experiences of lockdown such as observations on social distancing in neighbourhoods and how the relaxation of the lockdown rules was interpreted

- Experiences of accessing usual care provision for underlying health conditions or carer support

- Using new technologies including the benefits and challenges of adapting to online or remote ways of communication

The findings from the study will be reported in September 2020. For more information about the research, please visit the Equitable Place Based Health and Care Theme’s webpages or contact Paula Wheeler, EPHC Theme Manager and Neighbourhood Co-Ordinator: p.wheeler1@lancaster.ac.uk

Examining the impact of lockdown measures on people with Parkinson’s

The COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly challenging for those with pre-existing health conditions for whom the consequences of catching the disease may be more serious. Measures such as lockdown can have particularly deleterious effects due to the resulting loss of formal and informal support, and health and social care provision.

Professor Jane Simpson and Dr Fiona Eccles, working with Parkinson’s UK, have been examining the ways in which lockdown has been affecting people with Parkinson’s.

Parkinson’s UK, the largest charity supporting people with Parkinson’s in the UK, surveyed people affected by Parkinson’s in April-May 2020 during the most severe part of lockdown to find out the effects of the COVID-19 situation on the Parkinson’s community. The survey had two parts. The first part focused on the impact of the coronavirus restrictions on the person with Parkinson’s and the second part on the impact on family members, friends and carers. The first part was completed either by the people with the condition or by a family member, friend or carer on their behalf. The second part was completed only by family members, friends and carers. Finally, both people with Parkinson’s and their carers completed a validated measure of wellbeing, the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale. Following appropriate ethical approval, Lancaster University collaborated with Parkinson’s UK to analyse the data pertaining to the people with Parkinson’s and Parkinson’s UK analysed the family, friend and carer data. The findings are presented in a joint report to be published later this year.

Covid news from around the Faculty

We update our newsfeed regularly to reflect the work being undertaken by the Faculty.

More News