Talk of the town

If you’ve ever had a ‘barney’ with someone, wondered how Gaelic speakers produce certain sounds or why Scousers’ sentences go up at the end, you may want to read on.

Researchers search the globe for secrets of ageing well.

From Tai Chi and crosswords to the under-appreciated importance of hearing - Lancaster’s researchers are taking inspiration from across the world as they unlock some of the secrets to a healthy life in old age.

With an increasingly ageing population and people living longer but with long-term health conditions, researchers from various disciplines are working together to deliver outcomes that could change how we age.

Under The Centre for Ageing Research (C4AR), academics are conducting high-quality research into how we ensure older people experience an active and healthy age so periods of poor health start later.

With ambitions to reduce the gap between healthy lifespans and actual lifespans, C4AR is a leading international centre of excellence for ageing research looking at the causes, prevention and diagnosis of multiple conditions, including those most commonly associated with ageing such as frailty or Alzheimer’s and other dementias.

Chair of C4AR, Professor Carol Holland, is involved in the centre’s work focusing on the influence of social factors on frailty in older age and the link between physical frailty and mild cognitive impairment.

Professor Holland said: “As people get older, some become physically frail (for example, slowed walking speed and reduced muscle strength), and often memory and thinking skills can deteriorate. Although the two are different and can occur separately, often they are linked.

“The risk factors for each can be identified and addressed, but when a person has both physical frailty and mild cognitive impairment, it can increase their risk of hospitalisation, mortality and conditions like dementia.”

Professor Holland and colleagues questioned older people about the social aspects of their lives and measured frailty and resilience.

They found that those reporting loneliness, isolation, and less social interaction were much more likely to be physically frail.

Loneliness and depression are some of the most damaging factors in frailty because of their physiological impact.

Professor Holland said: “Loneliness is one of the most damaging factors in frailty, and this is because of its physiological impact. Being depressed is also harmful.

“Stress hormones are linked to the inflammation of our body’s systems, leading to the accumulation of muscle strength and mobility issues we see in frailty. This correlation reflects the findings of open access data across the UK and around the world.”

Loneliness isn’t the only long-term predictor of frailty and cognitive decline, with other risk factors including pollution, hearing loss, high alcohol use and a person’s education, employment, and social life.

“Mid-life hearing loss is a big predictor in dementia," said Professor Holland, "but also our lifetime intellectual engagement, so things like education, what we do for work and in our leisure time, can have huge long-term impacts on our health.

“That’s because our brain’s cognitive ability can be and needs to be challenged. It’s crucial to keep making new connections in our brains. This continues throughout our lives, so it’s never too late.”

“This builds what’s called ‘cognitive reserve’ which can counteract the loss of neurons – people with good reserve have alternative strategies to cope and compensate, as well as their brains having alternative ways of doing things when they have experienced any neurodegeneration.”

Professor Holland believes this should be widely understood and considered by people of all ages, and particularly employers.

“To live healthier lives for longer, with less frailty and increased cognitive ability, we need to keep strengthening our brains,” says Professor Holland. “People who challenge their brains regularly will have more cognitive reserve into older age. “This raises questions and responsibilities for employers. We need to change how people work so they aren’t doing repetitive tasks all day. It is vital brains are challenged. There are also benefits to potentially working for longer."

Professor Holland added: “Unfortunately underpinning all this is inequality, those with and without access to education, more challenging and typically higher-paid employment, extra-curricular activities, and the like.

“But if everyone is aware of the changes they can make within their lives, whether that’s keeping sociable or doing a hard crossword every day, it will help them in the end.”

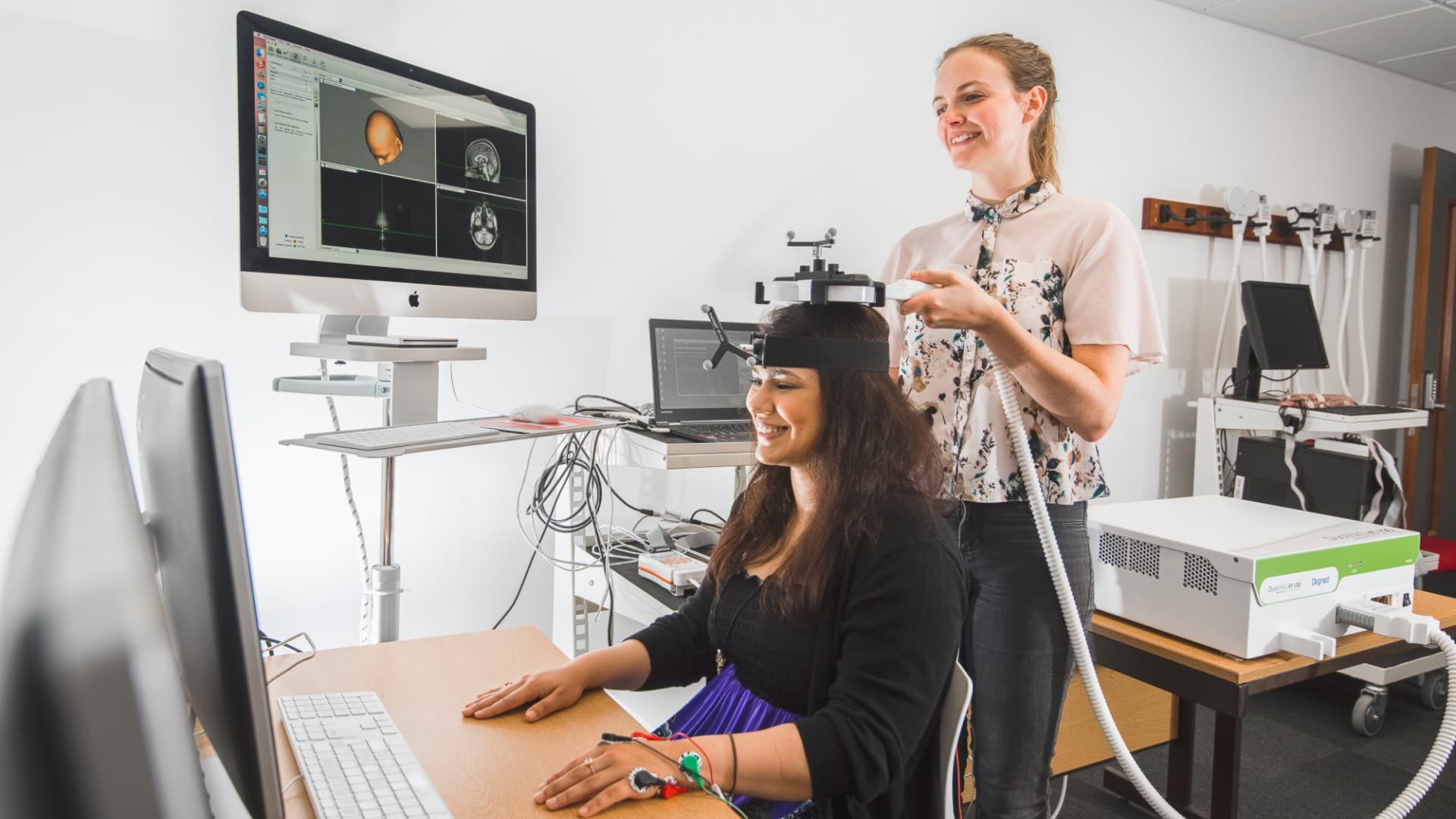

The widely unknown link between age-related hearing loss and dementia is being investigated by Doctor Helen Nuttall, who looks at forms of brain stimulation to improve memory during listening.

In 2020, The Lancet journal reported that hearing loss was the largest potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia. Research evidence suggests that those with untreated mild loss are two times more likely to develop dementia, increasing to three times more likely for those with untreated moderate hearing loss.

Dr Nuttall said: “As people get into their 70s, over 70 per cent of people have a degree of loss, but many are not aware of it or delay seeking help for many years.

“But if they have lived a number of years with hearing loss, this can lead to changes in the brain as it struggles to make sense of what it’s ‘heard’ through the ears.

“The auditory area of the brain starts to shrink because it’s not being used as much, which may have a knock-on effect on other areas of the brain. Attention and memory brain resources divert to listening to sound and speech, which reduces the memory resources available for other daily tasks.

Dr Nuttall added: “And while regular sight tests are the norm with vision loss widely accepted and wearing glasses seen as fashionable, the same can’t be said for regular hearing tests and the stigma attached to ageing and wearing hearing aids.

“We need earlier diagnosis before hearing loss has progressed undetected. I’d like to see routine hearing tests on the NHS starting in mid-life, so monitoring hearing health becomes as commonplace as monitoring blood pressure.”

But Dr Nuttall and her team are fighting back and are leading pioneering magnetic stimulation research to support the brain's memory resources when listening to speech.

They have been stimulating the brains of older adults with magnetic pulses while testing their auditory memory recall and associated brain function. Dr Nuttall and team are passionate about improving hearing health for better brain health as we age.

Reducing risk and uncovering the best forms of prevention and treatment for everyone underpins the Centre's research.

Meanwhile, Physicists at Lancaster are exploring the idea that ageing can be attributed to a decline in energy delivery within the body. Focusing on how energy reaches the brain, they have made an exciting breakthrough.

The cardiovascular system transports nutrients from food to each of the cells in the body, where a molecule called ATP is produced. Despite only accounting for 2% of the body's weight, the brain accounts for about 20% of the body's energy consumption and is especially sensitive to any malfunction in energy provision. There is growing evidence that malfunctioning of the neurovascular unit - which controls the blood supply to the neurons - is a critical player in the ageing of the brain.

Researchers led by Professor Aneta Stefanovska have proposed a non-invasive method of assessing the neurovascular unit's performance. Their findings, published in Brain Research Bulletin, were based on novel analysis methods developed by Lancaster's Nonlinear and Biomedical Physics Group. The blood oxygenation of living brains was measured using infrared light. The neuronal activity in the brain is associated with electrical activity, which was simultaneously measured on the scalp's surface.

Professor Stefanovska said: "The results promise a relatively simple and non-invasive method for assessing the state of the brain in healthy ageing and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease."

Professor Aneta Stefanovska

Public health researcher Dr Faraz Ahmed has spent his career looking at health inequalities and how views and attitudes to ageing and conditions such as dementia vary across and within minority ethnic groups.

His interest in understanding dementia, particularly in South Asian communities, has seen him work with focus groups in numerous cities across England, including York and Manchester.

Dr Ahmed said: “In some South Asian languages, for example, no words exist for dementia. Dementia is often seen as a part of ageing, and a lack of recognition and memory loss is considered a normal phase of ageing.

“This often means older people in these communities have worse health outcomes. If they don’t understand dementia, how can they talk to and explain to a health professional, particularly if there are additional cultural or language barriers.”

Dr Faraz Ahmed a the Alzheimer's European Conference in Helsinki

His findings have led him to an interest in social prescribing and how social farms could benefit marginalised groups. Social farms are an innovative use of agriculture to promote therapy, rehabilitation, social inclusion, and education. Over 400 such farms exist across the UK.

Dr Ahmed added: “We’re interested in exploring the impact social farms can have in greater detail. There is a reluctance in many communities to discuss dementia, so using green spaces and a connection to the environment can potentially stimulate conversations and raise awareness.

“Several councils are looking into the benefit of farms as a social prescribing tool, but we need to understand in what ways they are beneficial to people with dementia. I’m also interested in how inclusive these farms are and how accessible they are to all communities.”

Lancaster’s research is not only guiding healthcare practice and policies within the UK but is being used to shape healthcare provision around the world.

Lancaster University is at the heart of a global research community, and by working with other countries, we can share best practices in health and social care and evidence in research to better support people as they age wherever they are in the world.

Lecturer in ageing Doctor Qian Xiang is interested in global ageing issues, particularly promoting active and healthy ageing in the Global South, where most of the projected growth of the older population will be.

Dr Qian said: “I’m interested in what determines the process of ageing within a population and how different cultures and beliefs affect the ageing experiences.”

Her research on health has been on ageing-related conditions such as dementia. Her research sees her collaborate regularly with China, exploring how cultural aspects impact carer experiences and dementia therapies.

“One area of my work in dementia is assessing how music therapy and Tai Chi is effective in supporting the health and wellbeing of patients and their carers instead of more common pharmaceutical and medicinal treatments.”

She added: “Lancaster University is at the heart of a global research community, and by working with other countries, we’re able to share best practices in health and social care and evidence in research to better support people as they age wherever they are in the world.”