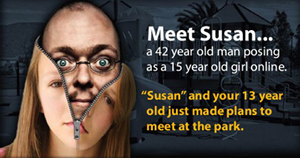

Corinne's current research (explained in her own words) looks at children's identities in a way which incorporates both their online and offline selves, researching how these are not exclusive entities, but interlinking parts of the self; and utilising theories surrounding cyborgs and childhood. We live in a digital age, and children are surfing the web before they can fully recognise any risks and dangers of, for example, chat rooms and social networking sites (and indeed, many adults are not aware of these risks and dangers either). Crucially, Corinne emphasises how the framing of abuse in an online environment constructs children as victims; through notions of 'victimhood' (Wattam, 1992; Parton, Thorpe, Wattam, 1996) and helplessness – a common trope of child internet safety. (Some examples of the (adult) predator, (child) prey opposition can be found later in this article, to demonstrate this idea.)

While Corinne's work is about increasing children's safety and protecting them against key online threats like child abuse media and child grooming, her research aims to provide children with the agency to protect themselves, an opportunity to take control of their own safety. Children are no longer simply victims, and can be empowered to begin protecting themselves, and hopefully also ask adults for support and advice too – Corinne's project is not a case of children becoming completely self-reliant, but a means of opening communication, bringing these issues to the forefront, and increasing safety through being able to talk about these online dangers, and talk to somebody if they feel uncomfortable or at risk in any way.

Corinne highlights the importance of her work through sharing some troubling facts: 'Very few children report harm caused to them and child maltreatment often goes undetected'. Corinne's research really excels in opening up opportunities for children to speak out should they feel at risk of harm, or have been harmed previously, through a child-friendly and invitingly modern approach to providing help and information. Culture is increasingly more reliant upon the digital, and Corinne's research embraces this, making the most of the technology available today in order to 'make children who experience significant harm or injury to be safer'. Use of these new technologies in this way not only provides children and adults with opportunities to become more technologically savvy through increasing awareness of the dangers present on the internet, but also provides a necessary update for the systems currently in place to protect children. In a world which is constantly developing, and inevitably becoming more and more reliant on new technologies, Corinne's work is similarly contemporary, and more in line with children's experiences of the world today, a digital world, with digital problems demanding digital solutions (May-Chahal et al, 2012).

Online child protection research has been funded by the EPSRC/ESRC on ISIS and EU funded iCOP projects, developing ethics-centred frameworks to monitor social networks and file sharing networks for the purpose of online child protection, supporting law enforcement agencies. This work aims to minimise risks of child exploitation, namely adults grooming children (adults wishing to 'sexually exploit children in chat rooms and web-based communities can use such forums to groom children and plan paedophilia-related activities'), and the distribution and sharing of child abuse media ('File-sharing systems are used to share child abuse media and hundreds of searches for child abuse media occur each second').