Children, young people and flooding: recovery and resilience

Flooding is the UK’s most serious civil contingency/hazard with more than 5 million properties at risk, and according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change we can expect more severe flooding over the coming years. The acute storms and floods in the UK during the winter of 2013/14, and most recently in Cumbria, have revealed a problem which is now understood to be chronic. We have been working with two groups of children who were affected by these severe winter floods: in rural South Ferriby (Humberside) and urban Staines-Upon-Thames (Thames Valley).

In emergencies while children and young people have particular needs, they can also display resilience and contribute to informing and preparing themselves, their families and their communities. It is vital that we understand the effects of emergencies on children and young people so that policy can develop in ways that take account of both their needs and their contributions to resilience building, thus reducing the impact of future emergencies. However, children and young people are missing, virtually invisible to the emergency planning process in the UK and more widely, for disasters including extreme weather events, such as severe flooding. In this project we have set out:

- To understand children’s experiences of the flooding, the impact on their lives, their resilience and the longer-term recovery process.

- To discover how children can best be supported in a flood and how to enhance their resilience to future emergencies.

- To influence emergency policy and practice to better meet the needs and build the resilience of children and young people.

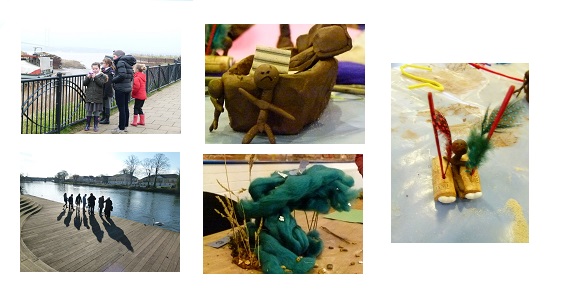

Our creative workshops began with ‘walking and talking’, then 3D modelling, culminating in drama and theatre. During the walks children took photographs of things or places that reminded them of the flood, including some of the remaining flood-damaged furniture and carpets in skips. There were also scenes of recovery like houses being rebuilt and renovated and on-going essential drainage works. It’s not easy for people who have never been flooded to understand what it is like. It’s even difficult for people who have been flooded to convey what they have gone through. We started sharing about what happened by using 3D art to create models of the flood experiences. The use of theatre and drama also opened up a creative and imaginative space for the children and young people, allowing them not only to reflect on what had happened but envisage different possibilities and have a voice in future flood management. The final stakeholder events used theatre as a powerful way for the children and young people to communicate their ideas for change to decision makers.

Materials have already been produced which aim to be a vehicle for children and young people’s engagement with policymakers and practitioners working in the area of emergency planning and management. These include the creation of Children and Young People’s Flood Manifestos which present their ideas for change around flood risk management and which were distributed at stakeholder events in the summer of 2015. We have also compiled the ‘Pledges’ that were made by the stakeholders who attended those events and were asked to commit to actions that they would take in response to the Flood Manifestos.

The flood project: a children’s manifesto for change is a film which highlights the children’s flood experiences and their involvement in this project as well as their ideas for action in the future. The Manifestos and the film are now being circulated among all the major agencies and authorities concerned with flood management.

For example, genetic data is no longer limited to clinical settings. Forms of DIY genetic testing offered by companies such as 23andMe provide opportunities for people to not only collect their own DNA sample and send it in for analysis, but also to analyse the results through online portals. Yet these alternative ways of engaging with genetic data have sparked concerns contributing to

For example, genetic data is no longer limited to clinical settings. Forms of DIY genetic testing offered by companies such as 23andMe provide opportunities for people to not only collect their own DNA sample and send it in for analysis, but also to analyse the results through online portals. Yet these alternative ways of engaging with genetic data have sparked concerns contributing to  Another important part of our work has involved organising and undertaking two citizens’ panels on health biosensors. One of the citizens’ panels was a participatory inquiry into the topics of personal genomics and home reproductive technologies entitled ‘Our Bodies Our Selves’. We invited 15 participants and 4 expert witnesses to learn about the technologies we are researching, and provided an opportunity for the participants, who often did not know about the technologies in detail, to ask critical questions and respond to the social, ethical and technical questions they provoke.

Another important part of our work has involved organising and undertaking two citizens’ panels on health biosensors. One of the citizens’ panels was a participatory inquiry into the topics of personal genomics and home reproductive technologies entitled ‘Our Bodies Our Selves’. We invited 15 participants and 4 expert witnesses to learn about the technologies we are researching, and provided an opportunity for the participants, who often did not know about the technologies in detail, to ask critical questions and respond to the social, ethical and technical questions they provoke.